This is a concept I developed a few years ago and have been meaning to getting around to publicly sharing. I make no claim to being the first to discover the technique, but was unable to find any documented evidence of the method being used previously. Essentially there are 2 fundamental issues with detecting base64 encoded strings, both of which often frustrate the blue team, my technique solves both problems. This post will go into the first problem, and the next will dive into the 2nd.

Let me just first point to how base64 encoded text is often detected by defenders.

Let’s say you’re looking to detect and alert on the encoded string “powershell”. Without understanding how the base64 algorithm works many will simple encode “powershell” in CyberChef or their tool of choice, and write a detection from the output. Let’s use an example:

% echo powershell|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbAo=

This is a common approach, and it’s already failing to detect the test string against a network traffic sample. If a detections team is not validating their signatures this non-functional string may be rolled out and a check box placed next to “Detect encoded use of ‘powershell’”. Did you catch the mistake?

The newline character got included in the encoding. So encoded base64 content such as “powershell(“ will not be detected.

% echo "powershell("|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbCgK

“powershell” WITH the accidentally included newline ends with “GVsbAo”, and “powershell(“ ends with “GVsbCgK” so the rule fails to detect just “powershell” and requires the newline to work. Leveling up slightly we redo it like so:

% echo -n powershell|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbA==

Now we can see that there’s actually a subset of the encoded base64 text that matches any content which trails “powershell”. We have to carefully trim the end of the encoded content to not force specific bytes to follow. A few more examples:

% echo -n "powershell "|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbCA=

% echo -n "powershell,"|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbCw=

% echo -n "powershell:"|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbDo=

We can see that the safe substring is “cG93ZXJzaGVsb” which actually decodes to the following:

% echo cG93ZXJzaGVsb|base64 -d

powershel%

So why is that we can’t search for the full string “powershell” as encoded and need to trim off the last character for a safe match?

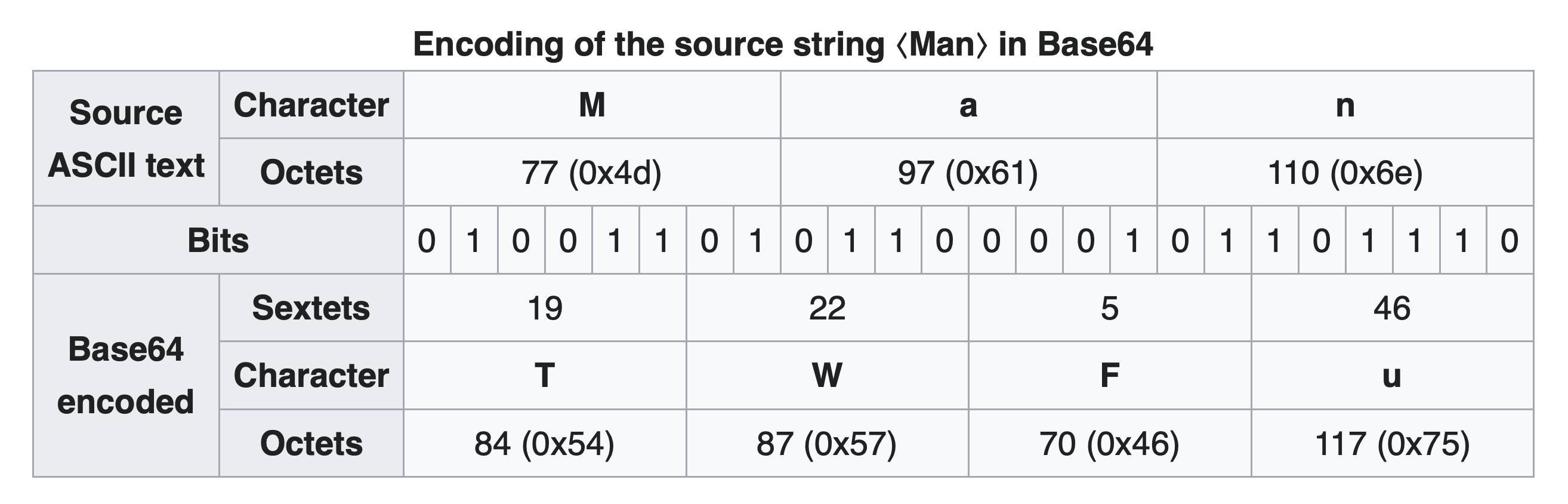

This is due to how base64 encoding works. It changes chunks of 3 bytes into 4 ASCII characters. When the length of a string is not divisible by 3, the final chunk is missing 1 or 2 characters. To handle this, the “=” padding characters are used. This is why base64 strings often have “=” or “==” as their endings. Yet you never see “===” at the end of an encoded string, because that’s an aligned chunk and has no padding.

Let’s examine the encoding of “powershell” and get a deeper understanding of base64 encoding.

8 x 3 = 6 x 4

We see that 3 bytes combine to 24 bits, these are then divided into 4 consecutive sets of 6 bits. We’re just slicing up the bits at a different boundary and 6 bits gives us a maximum of 64 different combinations instead of the 256 values that 8 bits can hold. With the chunks holding only 64 values we can then assign characters to each value and contain all 64 values in a limited character set that allows easy sending through email or other constrained environments.

So 26 upper case, 26 lower case, that gives us 52 values, then 10 numeric digits gets us up to 62. What 2 additional characters should we use for our base64 encoding? Usually it’s + and /, but there’s been several variant implementations as seen in the table here. Wikipedia Base64 Variants table

Ok so in summary. For safe base64 detection of encoded strings we must first be aware of the padding and alignment issues. If the string does not end at a chunk boundary we’ll need to trim off some of the text for a safe match. We also need to be careful not to accidentally include the newline when encoding a string or we’ll severly limit our potential matches.

But wait a minute, what if the text isn’t at the start of the line? Wouldn’t it get shifted over?

That’s correct, there’s a cyclic nature to the resulting encodings. For each string, there’s actually 3 completely different looking outputs depending on where it’s aligned. Using spaces with “powershell” we see:

% echo -n "powershell"|base64

cG93ZXJzaGVsbA==

% echo -n " powershell"|base64

IHBvd2Vyc2hlbGw=

% echo -n " powershell"|base64

ICBwb3dlcnNoZWxs

% echo -n " powershell"|base64

ICAgcG93ZXJzaGVsbA==

Observe how the 4th encoding with 3 space characters again aligns with the first encoding and they both contain “cG93” as the start of “powershell”. Also notice how the 3rd encoding with two spaces at the start ends at the boundary and doesn’t need any “=” padding characters. This means the 3rd encoding is the only one that safely contains the full “ell” at the end of the string match and will not be affected by the following byte. However instead of it’s final characters being compromised by the chunk boundary, we now find that the START of the string is unreliable and needs trimming.

Let’s demonstrate for each offset. At 1 byte shifted:

% echo -n " powershell"|base64

IHBvd2Vyc2hlbGw=

% echo -n ",powershell"|base64

LHBvd2Vyc2hlbGw=

% echo -n ";powershell"|base64

O3Bvd2Vyc2hlbGw=

We can see that the first character is influencing the output of the next 2 characters, this makes sense as it’s 8 bits can only affect the first 6 bits and the next 2. We need to trim the start of the encoded characters to “Bvd2Vyc2hlbG” for a safe matching substring. Let’s test that with some random initial characters:

% echo -n "Bvd2Vyc2hlbG"|base64 -d

?vW'6%

% echo -n "aBvd2Vyc2hlbG"|base64 -d

h?\??[%

% echo -n "aaBvd2Vyc2hlbG"|base64 -d

i?owershe%

Wow. So to safely detect “powershell” at an arbitrary offset we need to trim off different amounts of lead-up text which impact the fidelity of our detection rules. We can only safely detect “owershe”. Not cool.

One last time for the 2 byte starting offset:

% echo -n " powershell"|base64

ICBwb3dlcnNoZWxs

% echo -n "--powershell"|base64

LS1wb3dlcnNoZWxs

% echo -n ");powershell"|base64

KTtwb3dlcnNoZWxs

This makes sense, the first characer affects 2 of the output bytes, and the 2nd affects the 2nd and 3rd output bytes, but the final character in the 3 byte input chunk fully defines the last character which contains only it’s lowest 6 bits. So we have to trim THREE encoded characters to safely catch “powershell’ at a 2 byte boundary offset, what effect does this have on the content we’re matching on?

% echo -n "AAAwb3dlcnNoZWxs"|base64 -d

0owershell%

% echo -n "000wb3dlcnNoZWxs"|base64 -d

?M0owershell%

This time we’re detecting “owershell” but at least the ending is aligned and we’re catching “ell” at the end. The situation is dire. How can we deal with this?

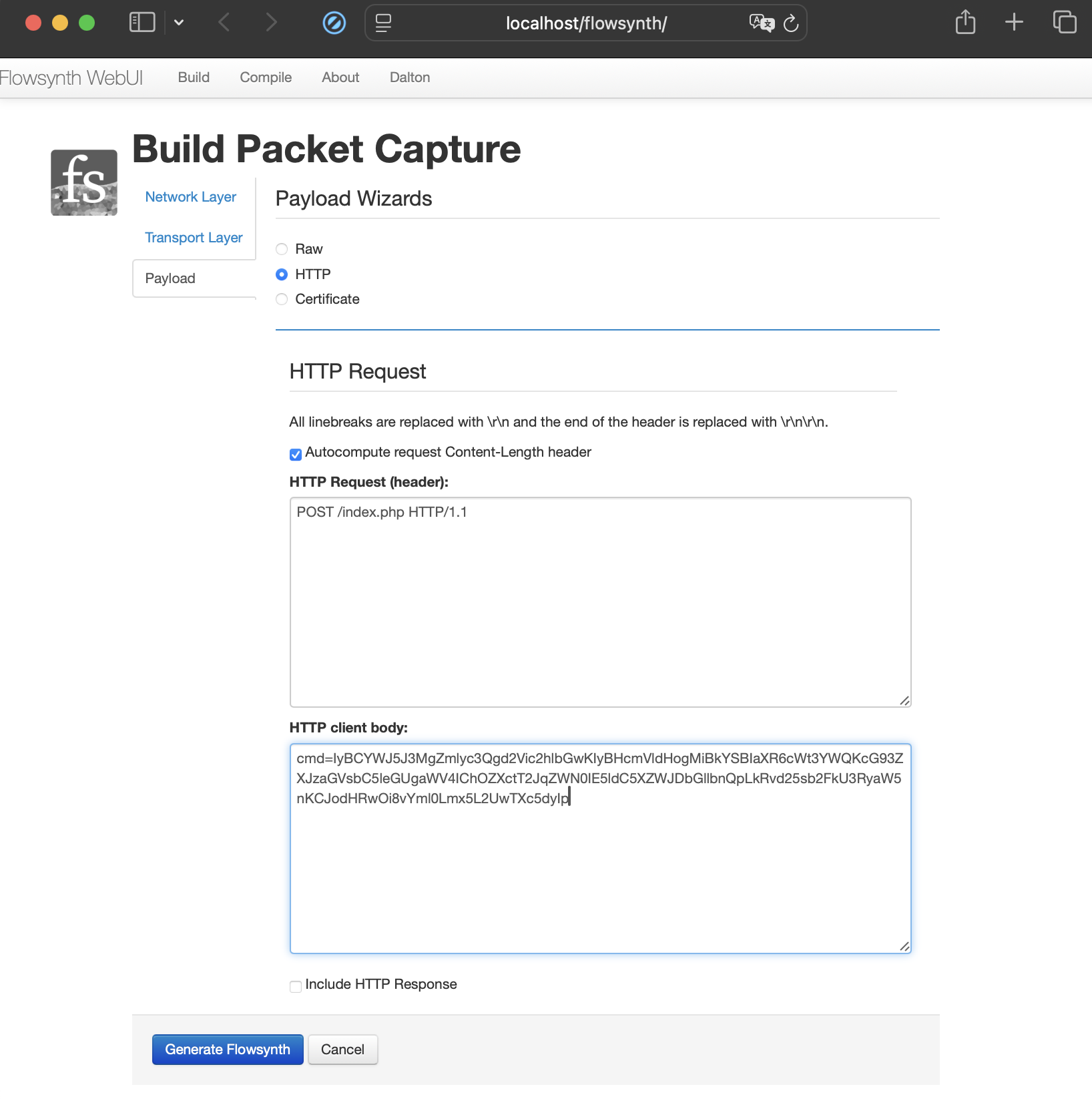

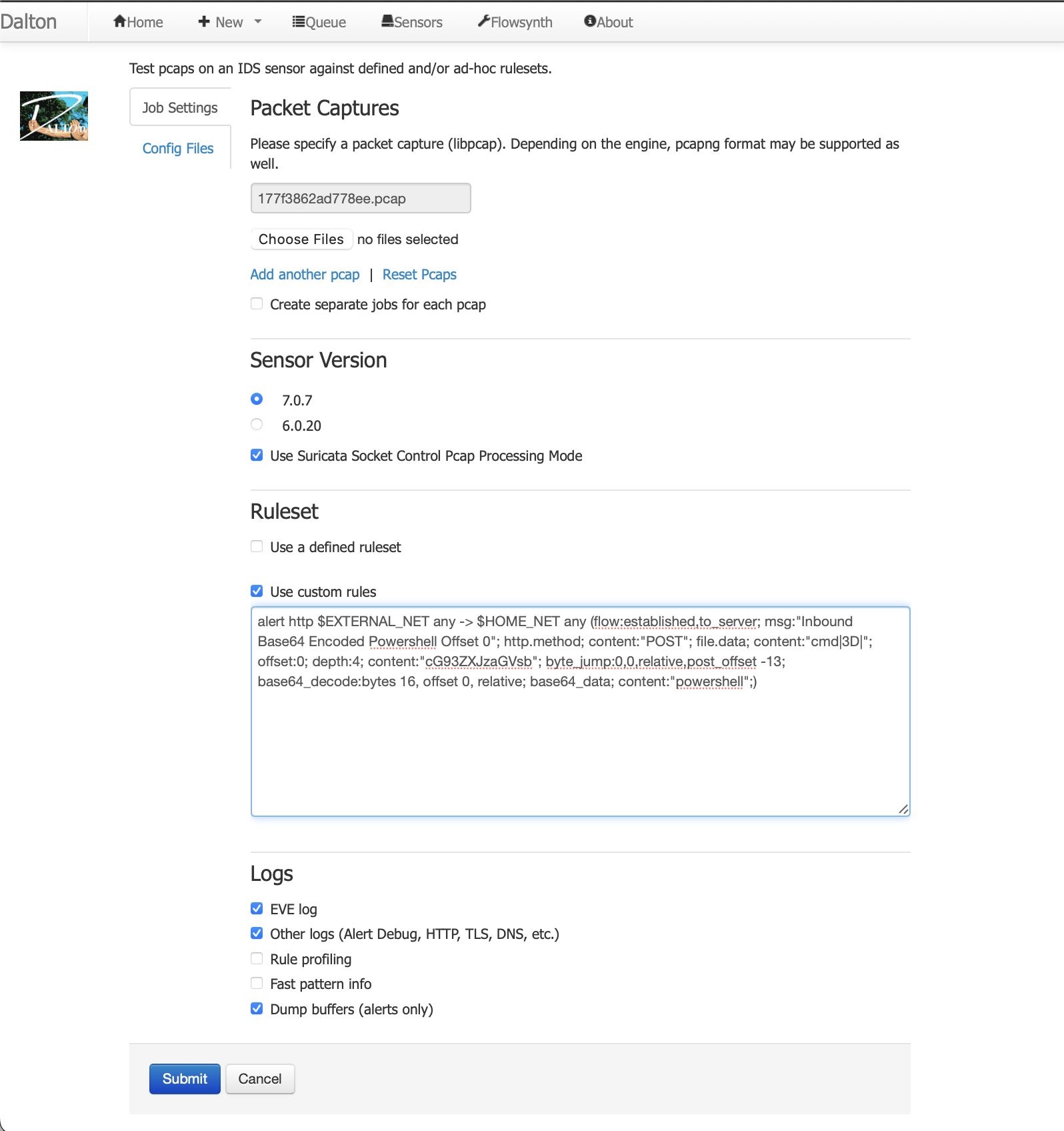

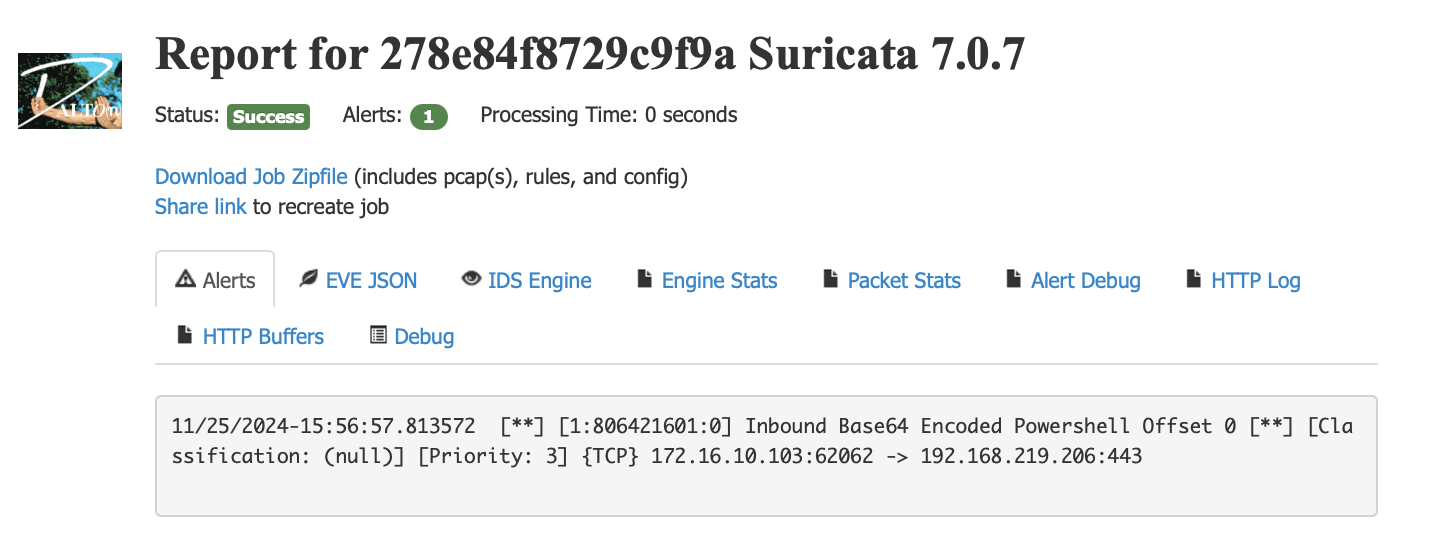

For an IDS device running Snort or Suricata we can use that partial match to then shift the input back the correct number of bytes, use the base64 decode function, and verify the full content match containing “powershell”. Let’s write some rules using Dalton and Flowsynth. 1

Creating some randomly offset powershell use in an HTTP POST body parameter….

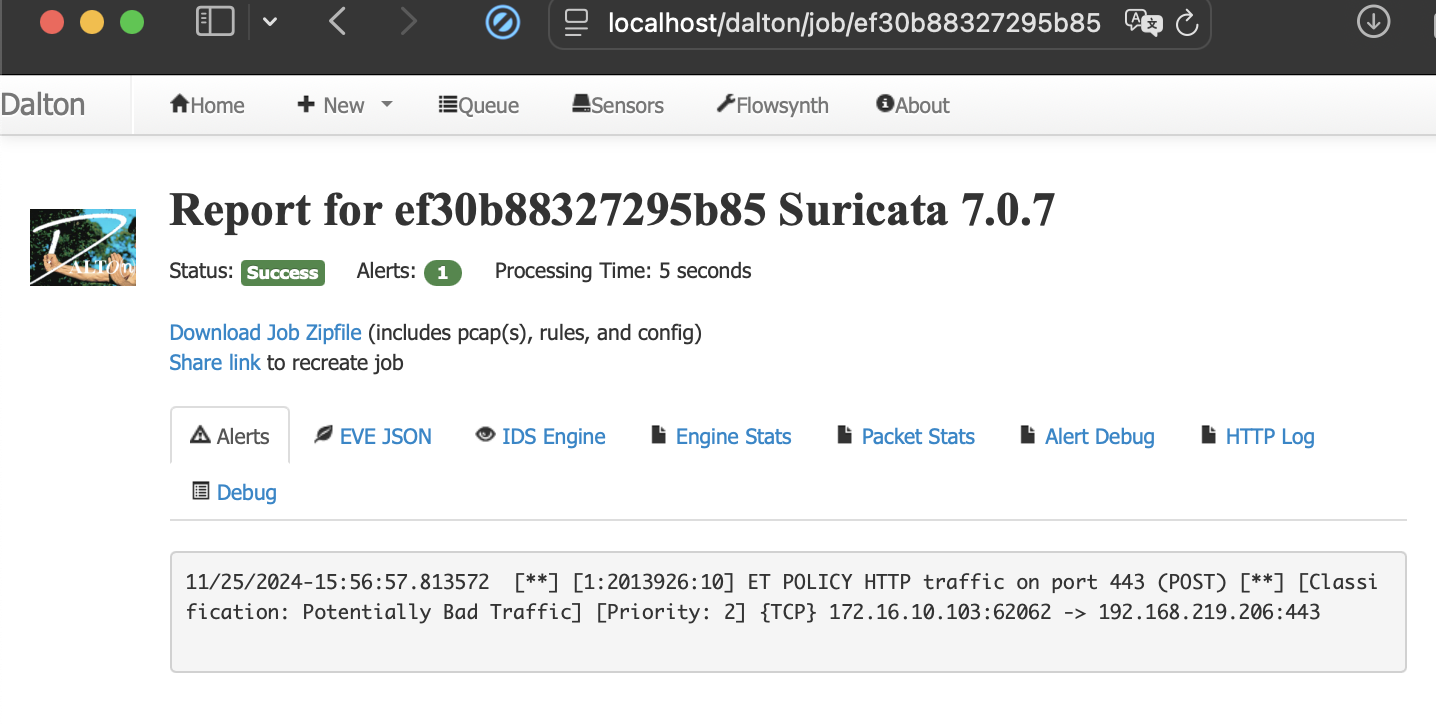

We run it against the Emerging Threats open source IDS ruleset and verify no existing detection.

Now the trick is to detect the partial content, jump BACK to align the base64 chunk start, decode the base64 data at the arbitrary position and then do a full internal content match verifying our detection with the decoded base64 content.

Using this technique we can now catch all 3 variations of encoded “powershell” at any arbitrary point in the data stream. Not only that, we can decode the full string and verify that it was not a false positive detection caused by the chopped bytes.

The final 3 Suricata rules to detect this content in our demo packets and the 3 demo packets are below.

alert http $EXTERNAL_NET any -> $HOME_NET any (flow:established,to_server; msg:"Inbound Base64 Encoded Powershell Offset 0"; http.method; content:"POST"; file.data; content:"cmd|3D|"; offset:0; depth:4; content:"cG93ZXJzaGVsb"; byte_jump:0,0,relative,post_offset -13; base64_decode:bytes 16, offset 0, relative; base64_data; content:"powershell";)

alert http $EXTERNAL_NET any -> $HOME_NET any (flow:established,to_server; msg:"Inbound Base64 Encoded Powershell Offset 1"; http.method; content:"POST"; file.data; content:"cmd|3D|"; offset:0; depth:4; content:"Bvd2Vyc2hlbG"; byte_jump:0,0,relative,post_offset -14; base64_decode:bytes 16, offset 0, relative; base64_data; content:"powershell";)

alert http $EXTERNAL_NET any -> $HOME_NET any (flow:established,to_server; msg:"Inbound Base64 Encoded Powershell Offset 2"; http.method; content:"POST"; file.data; content:"cmd|3D|"; offset:0; depth:4; content:"wb3dlcnNoZWxs"; byte_jump:0,0,relative,post_offset -16; base64_decode:bytes 16, offset 0, relative; base64_data; content:"powershell";)

PCAPs

In summary, we’ve gone beyond basic base64 detection strategies based using a better understanding of the encoding. We are now having a working knowledge of the chunk sizes, the bit alignments and how each character of input affects the output. We’ve understood the radical change in output text a single byte shift has, and seen the cyclic pattern that requires 3 unique string matches to safely detect our target string at arbitrary offsets. We’ve trimmed our encoded string to not be tainted by surrounding text, and we’ve used a negative byte_jump to move far enough back to base64 decode from the earliest chunk and verify that we have correctly made a true positive match. This is without using the PCRE functions and by using the barest IDS keywords we’ve kept this signature extremely performant and have minimized latency.

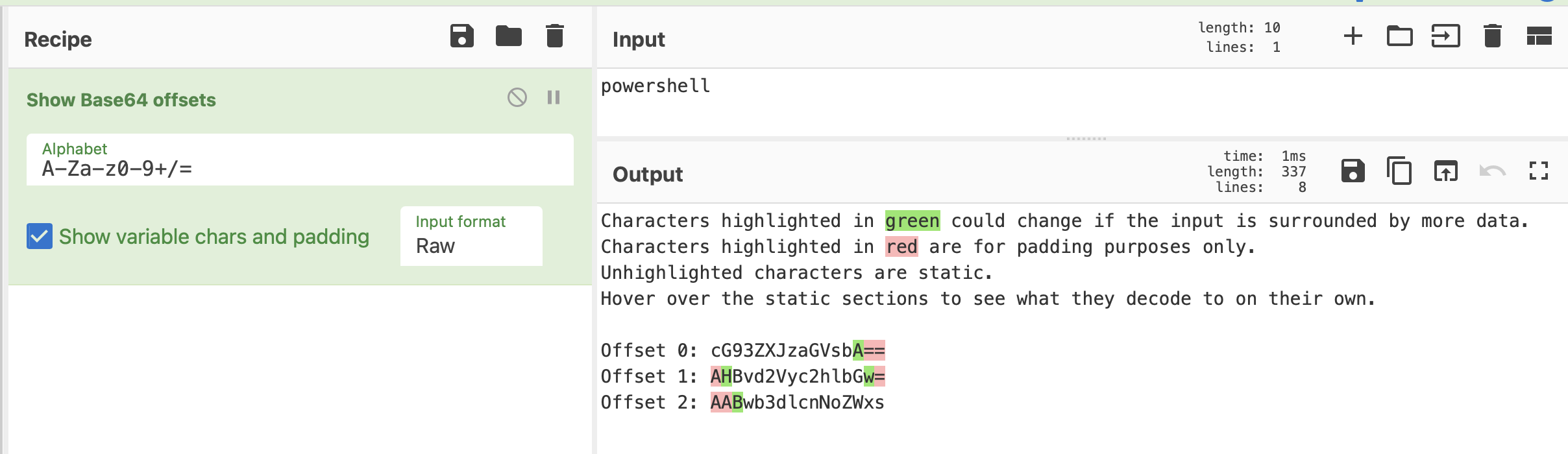

Now that we’ve done it manually we can optimize our process a bit, the CyberChef ‘Show Base64 offsets’ operation will visually demonstrate the process done earlier, with an input of “powershell” we can quickly redo the task of finding our safe encoded substrings.

However to truly reach Galaxy Brain with base64 content detection there’s a whole other mind wrecking concept to master, in Part II.